Tlaxcala and Cholula Background

Cholula

The Cholula massacre was one of the most ruthless actions of conquistador Hernan Cortes in his drive to conquer Mexico.

In October of 1519, Spanish conquistadors led by Hernan Cortes assembled the nobles of the Aztec city of Cholula in one of the city courtyards, where Cortes accused them of treachery. Moments later, Cortes ordered his men to attack the mostly unarmed crowd.

Outside of town, Cortes’ Tlaxcalan allies also attacked, as the Cholulans were their traditional enemies. Within hours, thousands of inhabitants of Cholula, including most of the local nobility, were dead in the streets. The Cholula massacre sent a powerful statement to the rest of Mexico, especially the mighty Aztec state and their indecisive leader, Montezuma II.

The City of Cholula

In 1519, Cholula was one of the most important cities in the Aztec Empire. Located not far from the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, it was clearly within the sphere of Aztec influence. Cholula was home to an estimated 100,000 people and was known for a bustling market and for producing excellent trade goods, including pottery. It was best known as a religious center, however. It was home to the magnificent Temple of Tlaloc, which was the largest pyramid ever built by ancient cultures, bigger even than the ones in Egypt.

It was best known, however, as the center of the Cult of Quetzalcoatl. This god had been around in some form since the ancient Olmec civilization, and worship of Quetzalcoatl had peaked during the mighty Toltec civilization, which dominated central Mexico from 900–1150 or so. The Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Cholula was the center of worship for this deity.

The Spanish and Tlaxcala

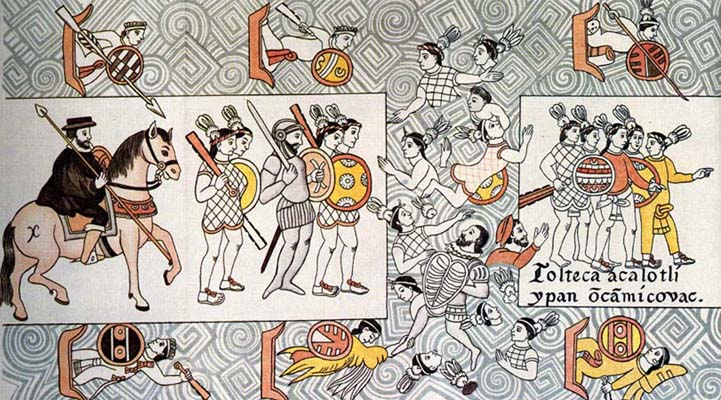

The Spanish conquistadors, under ruthless leader Hernan Cortes, had landed near present-day Veracruz in April of 1519. They had proceeded to make their way inland, making alliances with local tribes or defeating them as the situation warranted. As the brutal adventurers made their way inland, Aztec Emperor Montezuma II tried to threaten them or buy them off, but any gifts of gold only increased the Spaniards’ insatiable thirst for wealth. In September of 1519, the Spanish arrived in the free state of Tlaxcala. The Tlaxcalans had resisted the Aztec Empire for decades and were one of only a handful of places in central Mexico not under Aztec rule. The Tlaxcalans attacked the Spanish but were repeatedly defeated. They then welcomed the Spanish, establishing an alliance they hoped would overthrow their hated adversaries, the Mexica (Aztecs).

The Road to Cholula

The Spanish rested at Tlaxcala with their new allies and Cortes pondered his next move. The most direct road to Tenochtitlan went through Cholula and emissaries sent by Montezuma urged the Spanish to go through there, but Cortes’ new Tlaxcalan allies repeatedly warned the Spanish leader that the Cholulans were treacherous and that Montezuma would ambush them somewhere near the city.

While still in Tlaxcala, Cortes exchanged messages with the leadership of Cholula, who at first sent some low-level negotiators who were rebuffed by Cortes. They later sent some more important noblemen to confer with the conquistador. After consulting with the Cholulans and his captains, Cortes decided to go through Cholula.

Cortes Meets Xicotencatl, Tlaxcala Chief

From Cortés, Second Letter, pp. 58-59

At ten o’clock on the following day, Xicotencatl, Captain General of this Province, with about fifty of the principal persons belonging to it, came to me and solicited on the part of himself and of Magiscatzin (Governor of the Republic of Tlaxcala), who is the most important personage of the whole province, and on behalf of many other caciques or chiefs, that I would admit them into the royal service of your Highness, and to my friendship, and would pardon their past errors, as they had not known us, nor understood who we were; adding that they had already exerted their utmost strength, both by day and night, to avoid becoming subject to any power whatever; for at no period had this province ever been so, nor did it now own, nor had it at any former time acknowledged, a master; that they had lived free and unrestrained from time immemorial to the present moment; that they had always successfully defended themselves against at power of Moctezuma, and his father and ancestors, who had subjected the whole earth, but had never been able to reduce them to subjection, although they had hemmed them in on all sides, so that there was no passage left for them out of their own territory; that they were deprived of the use of salt, because it was not produced in any part of their country, nor were they able to go and procure it elsewhere; and for the same reason they were destitute of cotton cloth, as the cotton ant does not grow with them on account of the coldness of the climate, as well as of many other things of which they were in want, by reason of their being confined within such narrow limits.

At ten o’clock on the following day, Xicotencatl, Captain General of this Province, with about fifty of the principal persons belonging to it, came to me and solicited on the part of himself and of Magiscatzin (Governor of the Republic of Tlaxcala), who is the most important personage of the whole province, and on behalf of many other caciques or chiefs, that I would admit them into the royal service of your Highness, and to my friendship, and would pardon their past errors, as they had not known us, nor understood who we were; adding that they had already exerted their utmost strength, both by day and night, to avoid becoming subject to any power whatever; for at no period had this province ever been so, nor did it now own, nor had it at any former time acknowledged, a master; that they had lived free and unrestrained from time immemorial to the present moment; that they had always successfully defended themselves against at power of Moctezuma, and his father and ancestors, who had subjected the whole earth, but had never been able to reduce them to subjection, although they had hemmed them in on all sides, so that there was no passage left for them out of their own territory; that they were deprived of the use of salt, because it was not produced in any part of their country, nor were they able to go and procure it elsewhere; and for the same reason they were destitute of cotton cloth, as the cotton ant does not grow with them on account of the coldness of the climate, as well as of many other things of which they were in want, by reason of their being confined within such narrow limits.

Nevertheless, they preferred to suffer these privations, and considered it better for them, in order to enjoy their freedom and be subject to no one; and that in regard to myself, their feelings were the same; but that as they had already declared, they had tried their strength, and saw clearly that neither the force nor the skill that they had been able to command, profited them any thing, and they now sought to become the subjects of your Highness rather than perish and doom to destruction their houses, their women, and their children.

I satisfied them by saying, that they well knew the losses they had sustained were entirely owing to themselves; that I bad entered their territory in the belief that I was coming among friends, for the Cempoallans had assured me they were so, and wished to be so; and that I had sent in advance my messengers to inform them that I was coming, and of the pleasure their friendship would afford me; and that without returning me any answer while I was approaching with apparent security, they had attacked me on the road, killed two of my horses, and wounded others; and moreover, after fighting with me they had sent messengers, saying, that what had taken, place was contrary to their wishes and consent, certain communities having made the movement without their participation, but that they had reproved them for it, and desired my friendship.

Believing this to be true, I had told them that it gave me pleasure, and that on the next day I would visit them in their abodes as friends; and yet they had attacked me while and fought against me the whole day until on the way, the approach of night, notwithstanding I had earnestly desired peace. I also- reminded them of all they had done to oppose my progress, and many other matters, which I omit to mention that I may not weary your Highness. Finally, they remained, and acknowledged themselves as subjects and vassals of your Majesty, offering their persons and their estates for your royal service. This they carried into effect, and have remained faithful to the present time; and I believe they will always continue so, as your Majesty will hereafter see.

The Spanish and Tlaxcala

The Spanish conquistadors, under ruthless leader Hernan Cortes, had landed near present-day Veracruz in April of 1519. They had proceeded to make their way inland, making alliances with local tribes or defeating them as the situation warranted. As the brutal adventurers made their way inland, Aztec Emperor Montezuma II tried to threaten them or buy them off, but any gifts of gold only increased the Spaniards’ insatiable thirst for wealth. In September of 1519, the Spanish arrived in the free state of Tlaxcala. The Tlaxcalans had resisted the Aztec Empire for decades and were one of only a handful of places in central Mexico not under Aztec rule. The Tlaxcalans attacked the Spanish but were repeatedly defeated. They then welcomed the Spanish, establishing an alliance they hoped would overthrow their hated adversaries, the Mexica (Aztecs).

The Road to Cholula

The Spanish rested at Tlaxcala with their new allies and Cortes pondered his next move. The most direct road to Tenochtitlan went through Cholula and emissaries sent by Montezuma urged the Spanish to go through there, but Cortes’ new Tlaxcalan allies repeatedly warned the Spanish leader that the Cholulans were treacherous and that Montezuma would ambush them somewhere near the city.

While still in Tlaxcala, Cortes exchanged messages with the leadership of Cholula, who at first sent some low-level negotiators who were rebuffed by Cortes. They later sent some more important noblemen to confer with the conquistador. After consulting with the Cholulans and his captains, Cortes decided to go through Cholula.

Reception in Cholula

The Spanish left Tlaxcala on October 12 and arrived in Cholula two days later. The intruders were awed by the magnificent city, with its towering temples, well laid-out streets and bustling market. The Spanish got a lukewarm reception. They were allowed to enter the city (although their escort of fierce Tlaxcalan warriors was forced to remain outside), but after the first two or three days, the locals stopped bringing them any food. Meanwhile, city leaders were reluctant to meet with Cortes.

Before long, Cortes began to hear of rumors of treachery. Although the Tlaxcalans were not allowed in the city, he was accompanied by s ome Totonacs from the coast, who were allowed to roam freely. They told him of preparations for war in Cholula: pits dug in the streets and camouflaged, women and children fleeing the area, and more. In addition, two local minor noblemen informed Cortes of a plot to ambush the Spanish once they left the city.

Malinche’s Report

The most damning report of treachery came through Cortes’ mistress and interpreter, Malinche. Malinche had struck up a friendship with a local woman, the wife of a high-ranking Cholulan soldier. One night, the woman came to see Malinche and told her that she should flee immediately because of the impending attack. The woman suggested that Malinche could marry her son after the Spanish were gone. Malinche agreed to go with her in order to buy time and then turned the old woman over to Cortes. After interrogating her, Cortes was certain of a plot.

Cortes’ Speech

On the morning that the Spanish were supposed to leave (the date is uncertain, but was in late October 1519), Cortes summoned the local leadership to the courtyard in front of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, using the pretext that he wished to say goodbye to them before he left. With the Cholula leadership assembled, Cortes began to speak, his words translated by Malinche. Bernal Diaz del Castillo, one of Cortes’ foot soldiers, was in the crowd and recalled the speech many years later:

“He (Cortes) said: ‘How anxious these traitors are to see us among the ravines so that they can gorge themselves on our flesh. But our lord will prevent it.’…Cortes then asked the Caciques why they had turned traitors and decided the night before that they would kill us, seeing that we had done them nor harm but had merely warned them against…wickedness and human sacrifice, and the worship of idols…Their hostility was plain to see, and their treachery also, which they could not conceal…He was well aware, he said, that they had many companies of warriors lying in wait for us in some ravines nearby ready to carry out the treacherous attack they had planned…” (Diaz del Castillo, 198-199)

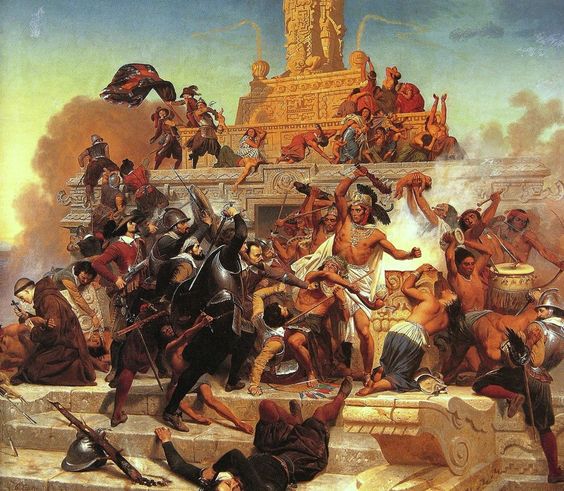

The Cholula Massacre

According the Diaz, the assembled nobles did not deny the accusations but claimed that they were merely following the wishes of Emperor Montezuma. Cortes responded that the King of Spain’s laws decreed that treachery must not go unpunished. With that, a musket shot fired: this was the signal the Spanish were waiting for.

According the Diaz, the assembled nobles did not deny the accusations but claimed that they were merely following the wishes of Emperor Montezuma. Cortes responded that the King of Spain’s laws decreed that treachery must not go unpunished. With that, a musket shot fired: this was the signal the Spanish were waiting for.

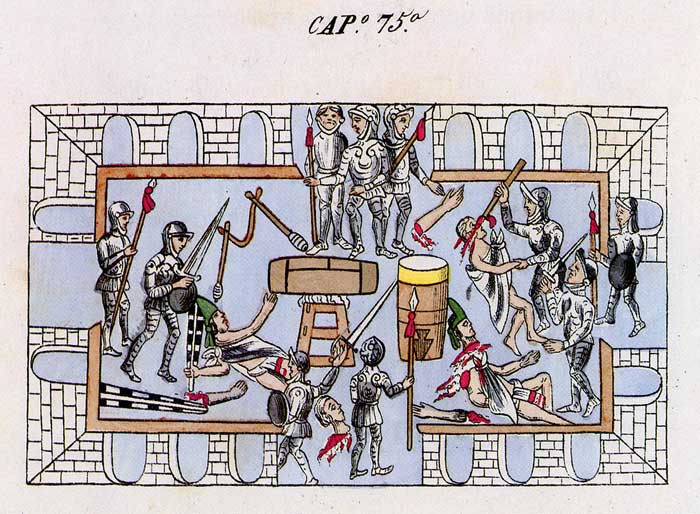

The heavily armed and armored conquistadors attacked the assembled crowd, mostly unarmed noblemen, priests and other city leaders, firing arquebuses and crossbows and hacking with steel swords. The shocked populace of Cholula trampled one another in their vain efforts to escape. Meanwhile, the Tlaxcalans, traditional enemies of Cholula, rushed into the city from their camp outside of town to attack and pillage. Within a couple of hours, thousands of Cholulans lay dead in the streets.

Aftermath of the Cholula Massacre

Still incensed, Cortes allowed his savage Tlaxcalan allies to sack the city and haul victims back to Tlaxcala as slaves and sacrifices. The city was in ruins and the temple burned for two days. After a few days, a few surviving Cholulan noblemen returned, and Cortes bade them tell the people that it was safe to come back. Cortes had two messengers from Montezuma with him, and they witnessed the massacre. He sent them back to Montezuma with the message that the lords of Cholula had implicated Montezuma in the attack and that he would be marching on Tenochtitlan as a conqueror. The messengers soon returned with word from Montezuma disavowing any involvement in the attack, which he blamed solely on the Cholulans and some local Aztec leaders.

Cholula itself was sacked, providing much gold for the greedy Spanish. They also found some stout wooden cages with prisoners inside who were being fattened up for sacrifice: Cortes ordered them freed. Cholulan leaders who had told Cortes about the plot were rewarded.

The Cholula Massacre sent a clear message to Central Mexico: the Spanish were not to be trifled with. It also proved to Aztec vassal states—of which many were unhappy with the arrangement—that the Aztecs could not necessarily protect them. Cortes hand-picked successors to rule Cholula while he was there, thus ensuring that his supply line to the port of Veracruz, which now ran through Cholula and Tlaxcala, would not be endangered.

When Cortes finally did leave Cholula in November of 1519, he reached Tenochtitlan without being ambushed. This raises the question of whether or not there had been a treacherous plan in the first place. Some historians question whether Malinche, who translated everything the Cholulans said and who conveniently provided the most damning evidence of a plot, orchestrated it herself. The historical sources seem to agree, however, that there was an abundance of evidence to support the likelihood of a plot.

Back to GODS OF WAR – SEASON TWO Historical Background